(H/T to Scott Aaronson for linking to the book and recommending it on his Shtetl Optimized. Thanks, Scott!)

Leopold Aschenbrenner’s Situational Awareness: The Decade Ahead (SA) is a very stimulating book. Whether you are an AI Doomer or an AI Accelerationist, somewhere in between, or (my preferred position) nowhere in that distribution, there’s something worth reading in it for everybody interested in the potential future of humanity and artificial intelligence. What makes it particularly worth reading is that it lays out a well-structured argument for why Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), the culmination point of AI research, is feasible within a decade. And potentially as early as 2027, if Aschenbrenner’s tracing of the trend lines is correct. In a world awash in hyperbolic claims about AI, as well as equally hyperbolic dismissals of AI, it’s nice to read a substantial work where someone sits down and does the work to make a full argument.

Aschenbrenner’s point in writing the book isn’t just to argue that AGI is both feasible AND near, it is to argue that it is critical for the survival of the world’s democracies (the collective West) that they develop and harness this technology before authoritarian regimes. For the purposes of this essay, I’m not interested in the national security implications: if you think Aschenbrenner is correct about the prospect of near-term AGI, I think his subsequent argument about what needs to be done is sound. What I’m interested in is (1) the external barriers to progress in the field, and (2) the possible futures where we don’t achieve AGI near term but get different levels of close to it.

First, let’s define Artificial General Intelligence. And define it in a pragmatic-functional way so we’d know it when we see it: a drop-in remote worker as capable as the 80th percentile human being working a given job, capable of achieving anything a human worker with a computer terminal and access to the internet can. It can learn any currently performed task you set it (develop software, create content, manage a business). It can be creative, inventive, and insightful. All of this at several orders of magnitude less cost per hour, orders of magnitude faster, and with access to orders of magnitude more information than any human. If we had one, we could have millions of them (the same computers you use to train a large-language model can deploy thousands or millions of that completed model running in parallel). And that would change the world.

Now to Aschenbrenner’s argument:

Deep learning AI systems, specifically those based on the Transformer architecture, have shown consistent progress and increases in capabilities, as shown by performance on widely-used and credible benchmarks.

The progress is due to orders of magnitude increases in computation on enormous amounts of data (essentially, the entirety of the Internet, filtered for duplication and spam).

This computation is not just physical compute time and data: it is also achieved by

algorithmic efficiency, finding ways to train the models more efficiently on the data we give them, enabling ‘deeper’ (there’s no other way to put it) comprehension, and

“unhobbling” - taking the models generated and both equipping them with the ability to make API calls, and fine tuning them to be general purpose agents rather than just chatbots.

Raw compute + data, algorithmic efficiency, and unhobbling can be traded off against each other: Each generation and partial generation of large-language models, for example, achieved the same result with fewer training cycles than the ones created before it (Google’s Gemini, for example, takes 1/10th the compute cost for inference that the initial release of GPT-4 did).

Effectively, one can spend less compute to get the same result with greater algorithmic efficiency, or use less efficient algorithms but more compute. Or unhobble the models with less efficient algorithms and less compute. Or, as Aschenbrenner argues the AI labs are doing, you can do all three at once.All the progress made in AI systems, using the Transformer architecture, has so far been relatively simple: computer scientists and software engineers messing around with Jupyter notebooks or having shower insights, not Albert Einstein contemplating the odd orbit of Mercury for months while slacking off in the Swiss patent office. It’s reasonable to expect that to continue. ##1

There is a massive rush of corporations and investors pouring money into this field, building bigger and bigger compute clusters to train ever larger models. Due to (3), (4), and (5), we should expect much more progress in the future, not less.

At a certain point, these models will cross a threshold that is, effectively, the AGI definition I gave above.

If you want to describe the above to a friend who isn't knowledgeable about AI, try the following shorthand description:

“there is a point we can reach with AI that is, for all intents and purposes, equivalent in intellect to a smart, educated human. Getting there is not a matter of having a series of Einstein's, or the singularity that was having almost all the world's foremost physicists gathered at Los Alamo working on just one thing. It's a matter of deploying ever more compute. And there is reason to think we are just about there.”

Before I read Aschenbrenner’s book, I had a naive “nah, not going to happen” attitude towards AGI. I thought it was a poorly defined concept, something AI Doomers and AI Accelerationists liked to talk about but that could, when one actually parsed out the semantics, conceal a conceptual confusion as bald as Quine’s “the round square copula at Berkeley” (in other words, a contradiction). To me, AGI seemed more like a philosophical abstraction than a tangible technological goal, a kind of intellectual bogeyman conjured up by those with extreme views on the future of artificial intelligence. The discussions around AGI seemed laden with a mix of ludicrous fear and ludicrous optimism, but without a clear, concrete understanding of what achieving such intelligence would entail or even mean in practical terms. But, reading Aschenbrenner and hearing Sam Altman describe the concept of AGI I outlined above, it seems much more possible than I had thought.

I’ll leave aside the discussion of whether AGI leads to artificial superintelligence (ASI) in short order for another time. I’ll just say that if you had AGI, and as many of them as you can get compute for, some extra step called ‘superintelligence’ seems superfluous.

I’ll also leave aside the ‘internal’ obstacles to AI progress for now to focus on the external ones. Just to outline, an internal obstacle is something internal to the way AI progress is being made now. A selection:

Scaling pays dividends at a slower and slower rate. Aschenbrenner’s argument, and those for near-term AGI in general, depend on a linear return on investment of compute. But what if progress simply tapers off to zero? Whatever potential might be out there at the far edge, its not economically feasible (today, or in the near future) to go and get it, even if the payoff was 100% economic growth per year past the threshold.

Algorithmic efficiency after a few more cycles of improvement hits a conceptual wall, one the AIs we have invented up to that point are not capable of helping us with. We would need a breakthrough on the order of AlexNet, or “Attention is all that you need”

Synthetic data is nowhere near as useful as real world data, and shows rapid declines in utility. Again, the AI models we have invented up to that point are not capable enough to help us.

Some may disagree, but I regard issues with hardware limitations (not enough chips) or energy consumption (not enough power for the data centers), all other things being equal, to be internal problems. If there is demand, those problems will get solved: chip fabs will be built, data centers will be wired up, natural gas will be fracked. Money will lure smart people to spend time on the details. But even granting that there is a linear path to AGI through scaling compute, algorithm efficiency, and unhobbling, we could still not get there for a century if…

1. No End User Makes Any Serious Money in the Near Term

The flow of money in the AI ecosystem looks like this:

Hardware Producers (NVIDIA, etc.) ← Data Centers (Microsoft, Amazon) ← AI Labs (OpenAI, Anthropic) ← End Users

Right now, the money is being made by the hardware producers like NVIDIA due to a temporary natural monopoly. The datacenter owners - and those constructing them - are also making money due to the massive demand for computation coming from the AI labs. The AI Labs are making some money, but aren’t properly commercial, profit-generating entities at the moment: they are investing everything back into buying ever more from the hardware producers and datacenters. And as far as I can tell, except around the margins, no early adopting end users are yet making a lot more money than they were before they started using AI. Plenty of influencers will claim to teach you how, but you know what they say about those who can: they Do, they do not Teach. ## 2

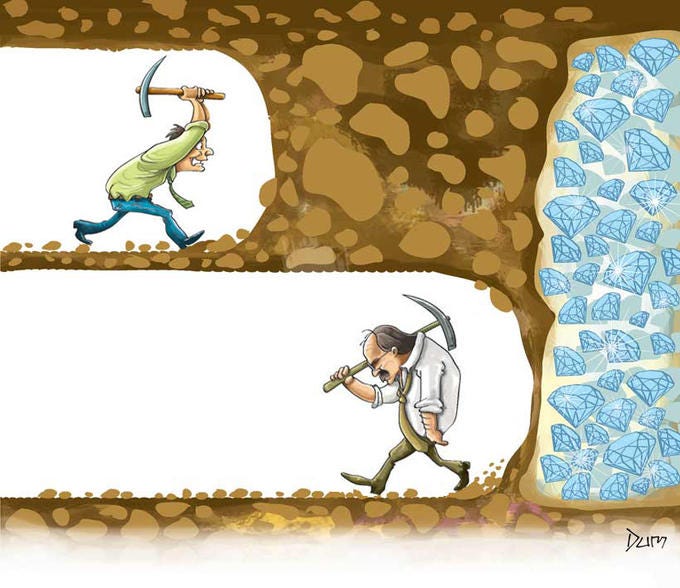

The primary external obstacle I see is if the end users just don’t get significant benefits from AI in some near term way. It might be the case, in its present implementation, that the primary benefit of generative AI accrues to the individual user, not to the firm. And that benefit may just be extra leisure time because the AI took care of all the grunt work of your job, and you aren’t motivated or aren’t in a position to generate more work. Not every job is widget manufacturing, where more hours put in or greater efficiency yields greater outputs in a linear fashion. If you work on projects given to you by managers, or cases that are created in a queue by customer requests, and just complete those projects faster, your rate limiting step is the supply of work and the overall system’s capacity to intake the finished work you produce. So you use ChatGPT to speed through your assignments, then watch more YouTube videos, play more smartphone games, or write more Substack essays (shhh….)

If the firms don’t get the benefits, then the rate of adoption of AI technology and the revenues from it slows. Then the labs aren’t making money, and the rush to invest in AI slows down. Progress slows, newer models aren’t produced at a rate sufficient to sustain interest, and it is a self-reinforcing doom loop that leads to another AI Winter. AGI might actually be just around the corner, but we just don’t get there. In the near term.

Or in Minecraft terms:

https://i.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/newsfeed/002/244/642/a5f.jpg

2. Financial Crisis

Another financial crisis, on the scale of the 2008 one, could hurt AI investment. When interest rates go up, high-risk investments like AI start looking less appealing compared to safer debt markets. Plus, spending on new AI services feels too risky, especially if there's no clear proof that they'll pay off. So, investors might lean towards safer bets, which could mean less money and development for AI. This external obstacle can compound with the former.

Though maybe by that point AI services are good enough to substitute for quite a bit of human labour, and the AI labs keep making money and keep investing thanks to a jobless recovery. Something like this happens in hydrocarbon dependent economies after a downturn in oil and gas prices: the end of a boom leads to consolidation and automation, which means that the subsequent boom makes money but employs fewer people.

3. Taiwan Showdown

Most dramatically of all, even if AI progress is roaring along at a good clip, GPT-5 is as much of an improvement (or more) over GPT-4 as GPT-4 was over GPT-3.5, and AI end users are making money, progress could still slam into a wall if Xi Jinping decides that reunification with the mainland cannot wait. The People's Liberation Army Navy blockades the island, then starts barraging it with conventional ballistic missiles. The world’s supply of bleeding edge semiconductors vanishes pretty much overnight - there is no significant store of semiconductors anywhere in the world and the manufacturers in Taiwan have enormous backlogs of orders.

And maybe during that conflict, TSMC’s fabrication facilities are destroyed, accidentally or deliberately. And if the PRC successfully topples Taiwan’s government, its hard to believe that TSMC’s workforce would stick around, if they had not already left by any means available before the shooting started. Even with an enormous outlay of government funds, it could take a decade or more to rebuild semiconductor production to the level it is currently at.

Almost But Not Quite. But …

As in many domains in life, there are not binary outcomes but a spectrum of outcomes. Think about all the effort being put into scaling up compute for the next generation of AI systems. And the next generation beyond that. The big unknown right now is when and if the capability growth of deep learning models, specifically those built on the Transformer architecture, starts to run out. Where you don't need a linearly scaling amount of compute for the next capability breakthrough, but a steep exponential. Or maybe progress just stops altogether except around the margins, and we just don't have AGI.

When I read people thinking about this, both the AI boosters and the skeptics are thinking about a single binary: either we have AGI or we don't. I think instead they should be thinking about the whole range of future we could have. Because, barring a Global Existential Risk coming to pass that sets back human technological civilization back an epoch or two, in not one of those futures are the current AI systems we are using as good as AI will ever get. Instead, we get ever greater refinement on much more advanced systems than we have now. It's not AGI, but it still would change the world.

Addendum: The Lindy Effect in Scientific Research

When we're going to reach the end of X is an interesting question. Consider algorithmic efficiency gains or the return on investment of the Scaling Hypothesis in AI training. Some smart people say we're nowhere near there yet, other people say we're just about there. Ignore the fact the latter have been wrong about this for going on a decade (“AI will never do X, AI will never do Y,... “). Who is right? When does progress run out?

Here I think it's worth considering the Lindy Effect heuristic. Simply stated, if you want to predict the longevity of a cultural artifact and know nothing else about it or contemporary conditions other than how long it has been around, expect it to be around as long again. So if the restaurant has been in existence for 10 years, expect 10 more years of life. If the book has been continuously in print for 200 years, expect 200 more years of publishing.

The heuristic wasn't proposed to cover fields of research, but I think it's not totally unwarranted. If a field has been generating new discoveries for five hundred years (physics, mathematics, astronomy) expect five more centuries of progress. If it's been generating discoveries for ten years, expect ten more years of progress. Now that feels ridiculously specific, but the point is not to have a perfect answer, but a starting point, a solid ground of ignorance from which to set out to greater accuracy.

Now if we trace contemporary deep learning progress back to AlexNet, twelve years afo, you wouldn't be mad to say “twelve more years of progress in this field, all else being equal” before stagnation sets in. And from there you can adjust your probability estimate back and forth (two years, four years, twelve years) as you learn more.